Indian Army

| Indian Army | |

|---|---|

Indian Army Seal |

|

| Founded | 15 August 1947 – Present |

| Country | India |

| Type | Army |

| Size | 1,100,000 Active personnel[1] 960,000 Reserve personnel[1] |

| Part of | Ministry of Defence Indian Armed Forces |

| Headquarters | New Delhi, India |

| Colour | Gold, red and black |

| Website | indianarmy.nic.in |

| Commanders | |

| Chief of the Army Staff | General V K Singh [2] |

| Notable commanders |

Field Marshal Cariappa Field Marshal Manekshaw |

The Indian Army (IA, Devanāgarī: भारतीय स्थलसेना, Bhāratīya Sthalsēnā) is the land based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. With about 1,100,000 soldiers in active service[1] and about 960,000 reserve troops[1] , the Indian Army is the world's second-largest standing army.[3][2] Its primary mission is to ensure the national security and defence of the Republic of India from external aggression and threats, and maintaining peace and security within its borders. It also conducts humanitarian rescue operations during natural calamities and other disturbances. The President of India serves as the Commander-in-Chief of the Army. The Chief of Army Staff (COAS), a General, is a four star commander and commands the Army. There is never more than one serving general at any given time in the Army. Two officers have been conferred the rank of Field Marshal, a 5-star rank and the officer serves as the ceremonial chief.

The Indian Army came into being when India gained independence in 1947, and inherited most of the infrastructure of the British Indian Army that were located in post-partition India. It is a voluntary service and although a provision for military conscription exists in the Indian constitution, it has never been imposed. Since independence, the Army has been involved in four wars with neighboring Pakistan and one with the People's Republic of China. Other major operations undertaken by the Army include Operation Vijay, Operation Meghdoot and Operation Cactus. Apart from conflicts, the Army has also been an active participant in United Nations peacekeeping missions.

Mission

|

||||||||||||

The Indian Army doctrine defines its as "The Indian Army is the land component of the Indian Armed Forces which exist to uphold the ideals of the Constitution of India." As a major component of national power, along with the Indian Navy and the Indian Air Force, the roles of the Indian Army are as follows:

- Primary: Preserve national interests and safeguard sovereignty, territorial integrity and unity of India against any external threats by deterrence or by waging war.

- Secondary: Assist Government agencies to cope with ‘proxy war’ and other internal threats and provide aid to civil authority when requisitioned for the purpose."[4]

History

British Indian Army

A Military Department was created in the Supreme Government of the East India Company at Kolkata in the year 1776, having the main function to sift and record orders relating to the Army issued by various Departments of the Govt of East India Co.[5]

With the Charter Act of 1833, the Secretariat of the Government of East India Company was reorganised into four Departments, including a Military Department. The Army in the Presidencies of Bengal, Bombay & Madras functioned as respective Presidency Army till April 1895, when the Presidency Armies were unified into a single Indian Army. For administrative convenience, it was divided into four Commands at that point of time viz. Punjab (including the North West Frontier), Bengal, Madras (including Burma) and Bombay (including Sind, Quetta and Aden).

The British Indian Army was a critical force in the primacy of the British Empire in both India, as well as across the world. Besides maintaining the internal security of the British Raj, the army fought in theaters around the world - Anglo-Burmese Wars, Anglo-Sikh Wars, Anglo-Afghan Wars, Opium Wars in China, Abyssinia, Boxer Rebellion in China. It is no coincidence that the decline of the British Empire started with the Independence of India.

First and Second World Wars

In the 20th century, the British Indian Army was a crucial adjunct to the British forces in both the World Wars.

1.3 million Indian soldiers served in World War I (1914–1918) for the Allies after the United Kingdom made vague promises of self-governance to the Indian National Congress for its support. Britain reneged on its promises after the war, following which the Indian Independence movement gained strength. 74,187 Indian troops were killed or missing in action in the war.[6]

The "Indianisation" of the British Indian Army began with the formation of the Prince of Wales Royal Indian Military College at Dehradun in March 1912 with the purpose of providing education to the scions of aristocratic and well to do Indian familes and to prepare selected Indian boys for admission into the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. Indian officers given a King's commission after passing out were posted to one of the eight units selected for Indianisation. Political pressure due to the slow pace of Indianisation, just 69 officers being commissioned between 1918 and 1932, led to the formation of the Indian Military Academy in 1932 and greater numbers of officers of Indian origin being commissioned.[7]

In World War II (1939–1945), 2.58 million Indian soldiers fought for the Allies, again after British promises of independence. Indian troops served in Eritrea, Abyssinia, North Africa, East Africa, Italy, Mesopotamia, Iran, Burma and Malaya, with 87,000 Indian soldiers losing their lives in the war. On the opposing side, an Indian National Army was formed under Japanese control, but had little effect on the war.

Inception

Upon independence and the subsequent Partition of India in 1947, four of the ten Gurkha regiments were transferred to the British Army. The rest of the British Indian Army was divided between the newly created nations of Republic of India and Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The Punjab Boundary Force, which had been formed to help police the Punjab during the partition period, was disbanded,[8] and Headquarters Delhi and East Punjab Command was formed to administer the area.

Conflicts and Operations

First Kashmir War (1947)

Almost immediately after independence, tensions between India and Pakistan began to boil over, and the first of three full-scale wars between the two nations broke out over the then princely state of Kashmir. Upon the Maharaja of Kashmir's reluctance to accede to either India or Pakistan, 'tribal' invasion of parts of Kashmir.[9] The men included Pakistan army regulars. Soon after, Pakistan sent in more of its troops to annex the State. The Maharaja, Hari Singh, appealed to India, and to Lord Mountbatten of Burma, the Governor General, for help. He signed the Instrument of Accession and Kashmir acceded to India (a decision ratified by Britain). Immediately after, Indian troops were airlifted to Srinagar and repelled the invaders.[9] This contingent included General Thimayya who distinguished himself in the operation and in years that followed, became a Chief of the Indian Army. An intense war was waged across the state and former comrades found themselves fighting each other. Both sides made some territorial gains and also suffered significant losses.

An uneasy UN sponsored peace returned by the end of 1948 with Indian and Pakistani soldiers facing each other directly on the Line of Control, which has since divided Indian-held Kashmir from Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Tensions between India and Pakistan, largely over Kashmir, have never since been entirely eliminated.

Inclusion of Hyderabad (1948)

After the partition of India, the State of Hyderabad, a princely-state under the rule of a Nizam, chose to remain independent. The Nizam, refused to accede his state to the Union of India. The following stand-off between the Government of India and the Nizam ended on 12 September 1948 when India's then deputy-Prime Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel ordered Indian troops to secure the state. With 5 days of low-intensity fighting, the Indian Army, backed by a squadron of Hawker Tempest aircraft of the Indian Air Force, routed the Hyderabad State forces. Five infantry battalions and one armored squadron of the Indian Army were engaged in the operation. The following day, the State of Hyderabad was proclaimed as a part of the Union of India. Major General Joyanto Nath Chaudhuri, who led the Operation Polo was appointed the Military Governor of Hyderabad (1948–1949) to restore law and order.

Liberation of Goa, Daman and Diu (1961)

Even though the British and French vacated all their colonial possessions in the Indian subcontinent, Portugal refused to relinquish control of its Indian colonies of Goa, Daman and Diu. After repeated attempts by India to negotiate with Portugal for the return of its territory were spurned by Portuguese prime minister and dictator, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, India launched Operation Vijay on 12 December 1961 to evict the Portuguese. A small contingent of its troops entered Goa, Daman and Diu to liberate and secure the territory. After a brief conflict, in which 31 Portuguese soldiers were killed, the Portuguese Navy frigate NRP Afonso de Albuquerque destroyed, and over 3000 Portuguese captured, Portuguese General Manuel António Vassalo e Silva surrendered to the Indian Army, after twenty-six hours and Goa, Daman and Diu joined the Indian Union.

Sino-Indian Conflict (1962)

The cause of the war was a dispute over the sovereignty of the widely-separated Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh border regions. Aksai Chin, claimed by India to belong to Kashmir and by China to be part of Xinjiang, contains an important road link that connects the Chinese regions of Tibet and Xinjiang. China's construction of this road was one of the triggers of the conflict.

Small-scale clashes between the Indian and Chinese forces broke out as India insisted on the disputed McMahon Line being regarded as the international border between the two countries. Despite sustaining losses, Chinese troops claim to have not retaliated to the cross-border firing by Indian troops.[10] China's suspicion of India's involvement in Tibet created more rifts between the two countries.[11]

In 1962, the Indian Army was ordered to move to the Thag La ridge located near the border between Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh and about three miles (5 km) north of the disputed McMahon Line. Meanwhile, Chinese troops too had made incursions into Indian-held territory and tensions between the two reached a new high when Indian forces discovered a road constructed by China in Aksai Chin. After a series of failed negotiations, the People's Liberation Army attacked Indian Army positions at the Thag La ridge. This move by China caught India by surprise and by 12 October, Nehru gave orders for the Chinese to be expelled from Aksai Chin. However, poor coordination among various divisions of the Indian Army and the late decision to mobilize the Indian Air Force in vast numbers gave China a crucial tactical and strategic advantage over India. On 20 October, Chinese soldiers attacked India in both the North-West and North-Eastern parts of the border and captured vast portions of Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh.

As the fighting moved beyond disputed territories, China called on the Indian government to negotiate, however India remained determined to regain lost territory. With no peaceful agreement in sight, China unilaterally withdrew its forces from Arunachal Pradesh. The reasons for the withdrawal are disputed with India claiming various logistical problems for China and diplomatic support to it from the United States, while China stated that it still held territory that it had staked diplomatic claim upon. The dividing line between the Indian and Chinese forces was christened the Line of Actual Control.

The poor decisions made by India's military commanders, and, indeed, its political leadership, raised several questions. The Henderson-Brooks & Bhagat committee was soon set up by the Government of India to determine the causes of the poor performance of the Indian Army. The report of China even after hostilities began and also criticized the decision to not allow the Indian Air Force to target Chinese transport lines out of fear of Chinese aerial counter-attack on Indian civilian areas. Much of the blame was also targeted at the incompetence of then Defence Minister, Krishna Menon who resigned from his post soon after the war ended. Despite frequent calls for its release, the Henderson-Brooks report still remains classified.[12]Neville Maxwell has written an account of the war.[13]

Indo-Pakistani War of 1965

A second confrontation with Pakistan took place in 1965, largely over Kashmir. Pakistani President Ayub Khan launched Operation Gibraltar in August 1965 during which several Pakistani paramilitary troops infiltrated into Indian-administered Kashmir and attempt to ignite an anti-India agitation in Jammu and Kashmir. Pakistani leaders believed that India, which was still recovering from the disastrous Sino-Indian War, would be unable to deal with a military thrust and a Kashmiri rebellion. However, the operation was a major failure since the Kashmiri people showed little support for such a rebellion and India quickly moved forces to drive the infiltrators out. Within a fortnight of the launch of the Indian counter-attack, most of the infiltrators had retreated back to Pakistan. Battered by the failure of Operation Gibraltar and expecting a major invasion by Indian forces across the border, Pakistan launched Operation Grand Slam on 1 September, invading India's Chamb-Jaurian sector. In retaliation, the India's Army launched major offensive throughout its border with Pakistan, with Lahore as its prime target. Though the Indian Army's break through of the final phases of Pakistani defence was considerably delayed due to logistical issues, the conflict was largely seen as a debacle for the Pakistani Army.[14]

Initially, the Indian Army met with considerable success in the northern sector. After launching prolonged artillery barrages against Pakistan, India was able to capture three important mountain positions in Kashmir. By 9 September, the Indian Army had made considerable in-roads into Pakistan. India had its largest haul of Pakistani tanks when the offensive of Pakistan's 1 Armoured Division was blunted at the Battle of Asal Uttar which took place on 10 September near Khemkaran. Six Pakistani Armoured Regiments took part in the battle against three Indian Armoured Regiments with inferior tanks. By the time the battle had ended, the 4th Indian Division had captured about 97 Pakistani tanks in either destroyed, or damaged, or in intact condition. This included 72 Patton tanks and 25 Chafees and Shermans. 32 of the 97 tanks, including 28 Pattons, were in running condition.[15] In comparison, the Indians lost only 32 tanks at Khemkaran-Bhikkiwind. About fifteen of them were captured by the Pakistan Army, mostly Sherman tanks. Pakistan's overwhelming defeat at the decisive battle of Assal Uttar hastened the end of the conflict.[16]

At the time of ceasefire declaration, India reported casualties of about 3,000 were killed. On the other hand, it was estimated that about 3,800 Pakistani soldiers were killed in the battle, 9,000 were wounded and about 2,000 were taken as prisoners of war.[17][18][19] About 300 Pakistani tanks were either destroyed or captured by India and an additional 150 were permanently put out of service. India lost a total of 190 tanks during the conflict and about 100 more had to undergo repair.[16] In all, India lost about half as many tanks as Pakistan lost during the war.[20] Given India's advantageous position at the end of the war, the decision to return back to pre-war positions, following the Tashkent Declaration, caused an outcry among the polity in New Delhi. It was widely believed that India's decision to accept the ceasefire was due to political factors, and not military, since it was facing considerable pressure from the United States and the UN to stop hostilities.[21]

Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

An independence movement broke out in East Pakistan which was brutally crushed by Pakistani forces. Due to large-scale atrocities against them, thousands of Bengalis took refuge in neighboring India causing a major refugee crisis there. In early 1971, India declared its full-support for the Bengali rebels, known as Mukti Bahini, and Indian agents were extensively involved in covert operations to aid them.

On 20 November 1971, Indian Army moved the 14 Punjab Battalion and 45 Cavalry into Garibpur, a strategically important town near India's border with East Pakistan, and successfully captured it. The following day, more clashes took place between Indian and Pakistani forces. Wary of India's growing involvement in the Bengali rebellion, the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) launched a pre-emptive strike on Indian military positions near its border with East Pakistan on 3 December. The aerial operation, however, failed to accomplish its stated objectives and caused India to declare a full-scale war against Pakistan the same day. By midnight, the Indian Army, accompanied by Indian Air Force, launched major military thrust into East Pakistan. The Indian Army won several battles on the eastern front including the decisive of battle of Hilli, which was the only front where the Pakistani Army was able to buildup considerable resistance.[22] India's massive early gains was largely attributed to the speed and flexibility with which Indian armored divisions moved across East Pakistan.[23]

Pakistan launched a counter-attack against India on the western front. On 4 December 1971, the A company of the 23rd Battalion of India's Punjab Regiment detected and intercepted the movement of the 51st Infantry Brigade of the Pakistani Army near Ramgarh, Rajasthan. The battle of Longewala ensued during which the A company, though being outnumbered, thwarted the Pakistani advance until the Indian Air Force directed its fighters to engage the Pakistani tanks. By the time the battle had ended, 34 Pakistani tanks and 50 armored vehicles were either destroyed or abandoned. About 200 Pakistani troops were killed in action during the battle while only 2 Indian soldiers lost their lives. Pakistan suffered another major defeat on the western front during the battle of Basantar which was fought from 4 December to 16th. By the end of the battle, about 66 Pakistani tanks were destroyed and 40 more were captured. In return, Pakistani forces were able to destroy only 11 Indian tanks. None of the numerous Pakistani offensives on the Western front materialized.[24] By 16 December, Pakistan had lost sizable territory on both eastern and western fronts.

Under the command of Lt. General J.S Arora, the three corps of the Indian Army, which had invaded East Pakistan, entered Dhaka and forced Pakistani forces to surrender on 16 December 1971, one day after the conclusion of the battle of Basantar. After Pakistan's Lt. General A.A.K. Niazi signed the Instrument of Surrender, India took more than 90,000 Pakistani prisoners of war. At the time of the signing of the Instrument of Surrender, 9,000 Pakistani soldiers were killed-in-action while India suffered only 2,500 battle-related deaths.[18] In addition, Pakistan lost 200 tanks during the battle compared to India's 80.[25]

In 1972, the Simla Agreement was signed between the two countries and tensions simmered. However, there were occasional spurts in diplomatic tensions which culminated into increased military vigilance on both sides.

Siachen conflict (1984)

The Siachen Glacier, though a part of the Kashmir region, was not officially demarcated on maps prepared and exchanged between the two sides in 1947. As a consequence, prior to the 1980s, neither India nor Pakistan maintained any permanent military presence in the region. However, Pakistan began conducting and allowing a series of mountaineering expeditions to the glacier beginning in the 1950s. By early 1980s, the government of Pakistan was granting special expedition permits to mountaineers and United States Army maps deliberately showed Siachen as a part of Pakistan. This practice gave rise to the contemporary meaning of the term oropolitics.

India, possibly irked by these developments, launched Operation Meghdoot in April 1984. The entire Kumaon Regiment of the Indian Army was airlifted to the glacier. Pakistani forces responded quickly and clashes between the two followed. Indian Army secured the strategic Sia La and Bilafond La mountain passes and by 1985, more than 1000 sq. miles of territory, 'claimed' by Pakistan, was under Indian control.[26] The Indian Army continues to control all of the Siachen Glacier and its tributary glaciers. Pakistan made several unsuccessful attempts to regain control over Siachen. In late 1987, Pakistan mobilized about 8,000 troops and garrisoned them near Khapalu, aiming to capture Bilafond La.[27] However, they were repulsed by Indian Army personnel guarding Bilafond. During the battle, about 23 Indian soldiers lost their lives while more than 150 Pakistani troops perished.[28] Further unsuccessful attempts to reclaim positions were launched by Pakistan in 1990, 1995, 1996 and 1999, most notably in Kargil that year.

India continues to maintain a strong military presence in the region despite extremely inhospitable conditions. The conflict over Siachen is regularly cited as an example of mountain warfare.[29] The highest peak in the Siachen glacier region, Saltoro Kangri, could be viewed as strategically important for India because of its immense altitude which could enable the Indian forces to monitor some Pakistani or Chinese movements in the immediate area.[30] Maintaining control over Siachen poses several logistical challenges for the Indian Army. Several infrastructure projects were constructed in the region, including a helipad 21,000 feet (6,400 m) above the sea level.[31] In 2004, Indian Army was spending an estimated US$2 million a day to support its personnel stationed in the region.[32]

Counter-insurgency activities

The Indian Army has played a crucial role in the past, fighting insurgents and terrorists within the nation. The army launched Operation Bluestar and Operation Woodrose in the 1980s to combat Sikh insurgents. The army, along with some paramilitary forces, has the prime responsibility of maintaining law and order in the troubled Jammu and Kashmir region. The Indian Army also sent a contingent to Sri Lanka in 1987 as a part of the Indian Peace Keeping Force.

Kargil conflict (1999)

In 1998, India carried out nuclear tests and a few days later, Pakistan responded by more nuclear tests giving both countries nuclear deterrence capability. Diplomatic tensions eased after the Lahore Summit was held in 1999. The sense of optimism was short-lived, however, since in mid-1999 Pakistani paramilitary forces and Kashmiri insurgents captured deserted, but strategic, Himalayan heights in the Kargil district of India. These had been vacated by the Indian army during the onset of the inhospitable winter and were supposed to reoccupied in spring. The regular Pakistani troops who took control of these areas received important support, both in the form of arms and supplies, from Pakistan. Some of the heights under their control, which also included the Tiger Hill, overlooked the vital Srinagar-Leh Highway (NH 1A), Batalik and Dras.

Once the scale of the Pakistani incursion was realized, the Indian Army quickly mobilized about 200,000 troops and Operation Vijay was launched. However, since the heights were under Pakistani control, India was in a clear strategic disadvantage. From their observation posts, the Pakistani forces had a clear line-of-sight to lay down indirect artillery fire on NH 1A, inflicting heavy casualties on the Indians.[33] This was a serious problem for the Indian Army as the highway was its main logistical and supply route.[34] Thus, the Indian Army's first priority was to recapture peaks that were in the immediate vicinity of NH1a. This resulted in Indian troops first targeting the Tiger Hill and Tololing complex in Dras.[35] This was soon followed by more attacks on the Batalik-Turtok sub-sector which provided access to Siachen Glacier. Point 4590, which had the nearest view of the NH1a, was successfully recaptured by Indian forces on 14 June.[36]

Though most of the posts in the vicinity of the highway were cleared by mid-June, some parts of the highway near Drass witnessed sporadic shelling until the end of the war. Once NH1a area was cleared, the Indian Army turned to driving the invading force back across the Line of Control. The Battle of Tololing, among other assaults, slowly tilted the combat in India's favor. Nevertheless, some of the posts put up a stiff resistance, including Tiger Hill (Point 5140) that fell only later in the war. As the operation was fully underway, about 250 artillery guns were brought in to clear the infiltrators in the posts that were in the line-of-sight. In many vital points, neither artillery nor air power could dislodge the outposts manned by the Pakistan soldiers, who were out of visible range. The Indian Army mounted some direct frontal ground assaults which were slow and took a heavy toll given the steep ascent that had to be made on peaks as high as 18,000 feet (5,500 m). Two months into the conflict, Indian troops had slowly retaken most of the ridges they had lost;[37][38] according to official count, an estimated 75%–80% of the intruded area and nearly all high ground was back under Indian control.

Following the Washington accord on 4 July, where Sharif agreed to withdraw Pakistani troops, most of the fighting came to a gradual halt, but some Pakistani forces remained in positions on the Indian side of the LOC. In addition, the United Jihad Council (an umbrella for all extremist groups) rejected Pakistan's plan for a climb-down, instead deciding to fight on.[39] The Indian Army launched its final attacks in the last week of July; as soon as the Drass subsector had been cleared of Pakistani forces, the fighting ceased on 26 July. The day has since been marked as Kargil Vijay Diwas (Kargil Victory Day) in India. By the end of the war, India had resumed control of all territory south and east of the Line of Control, as was established in July 1972 per the Shimla Accord. By the time all hostilities had ended, the number of Indian soldiers killed during the conflict stood at 527.[40] while more than 700 regular members of the Pakistani army were killed.[41] The number of Islamist fighters, also known as Mujahideen, killed by Indian Armed Forces during the conflict stood at about 3,000.[42]

United Nations Peacekeeping Missions

The Indian Army has undertaken numerous UN peacekeeping missions:[43]

- Angola, UNAVEM I, 1988–1991

- Angola, UNAVEM II, 1991–1995

- Angola, UNAVEM III, 1995–1997

- Angola, MONUA, 1997–1999

- Bosnia & Herzegovina, UNMIBH, 1995–2002

- Cambodia, UNAMIC, 1991–1992

- Cambodia, UNTAC, 1992–1993

- Central America, ONUCA, 1989–1992

- Congo, ONUC, 1960–1964

- El Salvador, ONUSAL, 1991–1995

- Ethiopia & Eritrea, UNMEE, 2000–2008

- Haiti, UNMIH, 1993–1996

- Haiti, UNSMIH, 1996–1997

- Haiti, UNTMIH, 1997

- Haiti, MIPONUH, 1997–2000

- Iran & Iraq, UNIIMOG, 1988–1991

- Iraq & Kuwait, UNIKOM, 1991–2003

- Israel, UNDOF

- Liberia, UNOMIL, 1993–1997

- Lebanon, UNOGL, UNIFIL, 1958

- Middle East, UNEF I, 1956–1967

- Mozambique, ONUMOZ, 1992–1994

- Namibia, UNTAG, 1989–1990

- Rwanda, UNAMIR, 1993–1996

- Sierra Leone, UNOMSIL, 1998–1999

- Sierra Leone, UNAMSIL, 1999–2005

- Somalia, UNOSOM, 1993–1995

- Yemen, UNYOM, 1963–1964

The Indian army also provided paramedical units to facilitate the withdrawal of the sick and wounded in the Korean War.

Major Exercises

Operation Brasstacks

Operation Brasstacks was launched by the Indian Army in November 1986 to simulate a full-scale war on the western border. The exercise was the largest ever conducted in India and comprised nine infantry, three mechanised, three armoured and one air assault division, and included three armoured brigades. Amphibious assault exercises were also conducted with the Indian Navy. Brasstacks also allegedly incorporated nuclear attack drills. It led to tensions with Pakistan and a subsequent rapprochement in mid-1987.[44][45]

Operation Parakram

After the 13 December 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament, Operation Parakram was launched in which tens of thousands of Indian troops were deployed along the Indo-Pakistan border. India blamed Pakistan for backing the attack. The operation was the largest military exercise carried out by any Asian country. Its prime objective is still unclear but appears to have been to prepare the army for any future nuclear conflict with Pakistan, which seemed increasingly possible after the December attack on the Indian parliament.

Operation Sanghe Shakti

It has since been stated that the main goal of this exercise was to validate mobilisation strategies of the Ambala-based II Strike Corps. Air support was a part of this exercise, and an entire battalion of paratroops was paradropped during the conduct of the war games, with allied equipment. Some 20,000 soldiers took part in the exercise.

Exercise Ashwamedha

Indian Army tested its network centric warfare capabilities in the exercise Ashwamedha. The exercise was held in the Thar desert, in which over 300,000 troops participated.[46]. Asymmetric warfare capability was also tested by the Indian Army during the exercise.[47]

Structure of the Indian Army

Initially, the army's main objective was to defend the nation's frontiers. However, over the years, the army has also taken up the responsibility of providing internal security, especially in insurgent-hit Kashmir and north-east.

The army has a strength of about a million troops and fields 34 divisions. Its headquarters is located in the Indian capital New Delhi and it is under the overall command of the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), currently General V K Singh, PVSM, AVSM, YSM, ADC

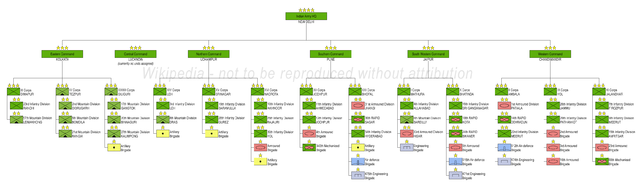

Commands

The army operates 6 tactical commands . Each command is headed by General Officer Commanding-in-Chief with the rank of Lieutenant General. Each command is directly affiliated to the Army HQ in New Delhi. These commands are given below in their correct order of raising, location (city) and their commanders. There is also one training command known as ARTRAC. The staff in each Command HQ is headed by Chief Of Staff (COS) who is also an officer of Lieutenant General rank.

Corps

A corps is an army field formation responsible for a zone within a command theatre. There are three types of corps in the Indian Army: Strike, Holding and Mixed. A command generally consists of two or more corps. A corps has Army divisions under its command. The Corps HQ is the highest field formation in the army.

The Arjun MBT is entering service with 140 Armoured Brigade in Jaisalmer.

|

|

|

Regimental Organisation

In addition to this (not to be confused with the Field Corps mentioned above) are the Regiments or Corps or departments of the Indian Army. The corps mentioned below are the functional divisions entrusted with specific pan-Army tasks.

Arms

The Indian Territorial Army has units from a number of corps which serve as a part-time reserve. Services

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Other Field Formations

-

- Division: An Army Division is an intermediate between a Corps and a Brigade. It is the largest striking force in the army. Each Division is headed by [General Officer Commanding] (GOC) in the rank of Major General. It usually consists of 15,000 combat troops and 8,000 support elements. Currently, the Indian Army has 34 Divisions including 4 RAPID (Re-organised Army Plains Infantry Divisions) Action Divisions, 18 Infantry Divisions, 10 Mountain Divisions, 3 Armoured Divisions and 2 Artillery Divisions. Each Division composes of several Brigades.

- Brigade: A Brigade generally consists of around 3,000 combat troops with supporting elements. An Infantry Brigade usually has 3 Infantry Battalions along with various Support Arms & Services. It is headed by a Brigadier, equivalent to a Brigadier General in some armies. In addition to the Brigades in various Army Divisions, the Indian Army also has 5 Independent Armoured Brigades, 15 Independent Artillery Brigades, 7 Independent Infantry Brigades, 1 Independent Parachute Brigade,3 Independent Air Defence Brigades, 2 Independent Air Defence Groups and 4 Independent Engineer Brigades. These Independent Brigades operate directly under the Corps Commander (GOC Corps).

- Battalion: A Battalion is commanded by a Colonel and is the Infantry's main fighting unit. It consists of more than 900 combat personnel.

- Company: Headed by the Major, a Company comprises 120 soldiers.

- Platoon: An intermediate between a Company and Section, a Platoon is headed by a Lieutenant or depending on the availability of Commissioned Officers, a Junior Commissioned Officer, with the rank of Subedar or Naib-Subedar. It has a total strength of about 32 troops.

- Section: Smallest military outfit with a strength of 10 personnel. Commanded by a Non-commissioned officer of the rank of Havildar Major or Sergeant Major.

Regiments

Infantry Regiments

There are several battalions or units associated together in an infantry regiment. The infantry regiment in the Indian Army is a military organisation and not a field formation. All the battalions of a regiment do not fight together as one formation, but are dispersed over various formations, viz. brigades, divisions and corps. An infantry battalions serves for a period of time under a formation and then moves to another, usually in another sector or terrain when its tenure is over. Occasionally, battalions of the same regiment may serve together for a tenure.

Most of the infantry regiments of the Indian Army originate from the old British Indian Army and recruit troops from a region or of specific ethnicities.

The list of infantry regiments of the Indian Army are:

- Brigade of the Guards

- The Parachute Regiment

- Mechanised Infantry Regiment

- Punjab Regiment

- Madras Regiment

- The Grenadiers

- Maratha Light Infantry

- Rajputana Rifles

- Rajput Regiment

- Jat Regiment

- Sikh Regiment

- Sikh Light Infantry

- Dogra Regiment

- Garhwal Rifles

- Kumaon Regiment

- Assam Regiment

- Bihar Regiment

- Mahar Regiment

- Jammu & Kashmir Rifles

- Jammu & Kashmir Light Infantry

- Naga Regiment

- 1 Gorkha Rifles (The Malaun Regiment)

- 3 Gorkha Rifles

- 4 Gorkha Rifles

- 5 Gorkha Rifles (Frontier Force)

- 8 Gorkha Rifles

- 9 Gorkha Rifles

- 11 Gorkha Rifles

- Ladakh Scouts

Artillery Regiments

The Regiment of Artillery constitutes a formidable operational arm of Indian Army. Historically it takes its lineage from Moghul Emperor Babur who is popularly credited with introduction of Artillery in India, in the Battle of Panipat in 1526. However evidence of earlier use of gun by Bahmani Kings in the Battle of Adoni in 1368 and King Mohammed Shah of Gujrat in fifteenth century have been recorded. Indian artillery units were disbanded after the 1857 rebellion and reformed only during the Second World War.

Armoured Regiments

There are 97 armoured regiments in the Indian Army

Indian Army Staff and Equipment

Strength

| Indian Army statistics | |

| Active Troops | 1,100,000 |

| Reserve Troops | 960,000 |

| Indian Territorial Army | 787,000** |

| Main battle tanks | 5,000 |

| Artillery | 3,200 |

| Ballistic missiles | ~100 (Agni-I, Agni-II, Agni-III) |

| Ballistic missiles | ~1,000 Prithvi missile series |

| Cruise missiles | ~1,000 BrahMos |

| Aircraft | ~1,500 |

| Surface-to-air missiles | 100,000 |

** includes 387,000 1st line troops and 400,000 2nd line troops

Statistics

- 4 RAPID (Reorganised Army Plains Infantry Divisions)

- 18 Infantry Divisions

- 10 Mountain Divisions

- 3 Armoured Divisions

- 2 Artillery Divisions

- 3 Air Defence Brigades + 2 Surface-to-Air Missile Groups

- 5 Independent Armoured Brigades

- 15 Independent Artillery Brigades

- 7 Independent Infantry Brigades

- 2 Parachute Brigade

- 4 Engineer Brigades

- 41 Army Aviation Helicopter Units

Sub-Units

- 93 Tank Regiments

- 50 Airborne Battalions

- 50 Artillery Regiments

- 41 Infantry Battalions + 32 Para (SF) Battalions

- 32 Mechanised Infantry Battalions

- 23 Combat Helicopter Units

- 50 Air Defence Regiments

Rank structure

The various rank of the Indian Army are listed below in descending order:

Commissioned Officers

- Field Marshal1

- General (the rank held by Chief of Army Staff)

- Lieutenant-General

- Major-General

- Brigadier

- Colonel

- Lieutenant-Colonel

- Major

- Captain

- Lieutenant

Junior Commissioned Officers (JCOs)

- Subedar Major/Honorary Captain3

- Subedar/Honorary Lieutenant3

- Subedar Major

- Subedar

- Naib Subedar

Non Commissioned Officers (NCOs)

- Regimental Havildar Major2

- Regimental Quarter Master Havildar2

- Company Havildar Major

- Company Quarter Master Havildar

- Havildar

- Naik

- Lance Naik

- Sepoy

Notes:

- Only two officers have been made Field Marshall so far: Field Marshal K M Cariappa—the first Indian Commander-in-Chief (a post since abolished)—and Field Marshal S H F J Manekshaw, the Chief of Army Staff during the Army in the 1971 war with Pakistan.

- This has now been discontinued. Non-Commissioned Officers in the rank of Havildar are elible for Honorary JCO ranks.

- Given to Outstanding JCO's Rank and pay of a Lieutenant, role continues to be of a JCO.

Combat Doctrine

The current combat doctrine of the Indian Army is based on effectively utilizing holding formations and strike formations. In the case of an attack, the holding formations would contain the enemy and strike formations would counterattack to neutralize enemy forces. In the case of an Indian attack, the holding formations would pin enemy forces down whilst the strike formations attack at a point of Indian choosing. The Indian Army is large enough to devote several corps to the strike role. Currently, the army is also looking at enhancing its special forces capabilities. With the role of India increasing and the requirement for protection of India's interest in far off shores become important, the Indian Army and Indian Navy is jointly planning to set up a marine brigade.[49]

Equipment

Most of the army equipment is imported, but efforts are being made to manufacture indigenous equipment. The Defence Research and Development Organisation has developed a range of weapons for the Indian Army ranging from small arms, artillery, radars and the Arjun tank. All Indian Military small-arms are manufactured under the umbrella administration of the Ordnance Factory Board, with principal Firearm manufacturing facilities in Ichhapore, Cossipore, Kanpur, Jabalpur and Tiruchirapalli. The Indian National Small Arms System (INSAS) rifle, which is successfully inducted by Indian Army since 1997 is a product of the Ishapore Rifle Factory, while ammunition is manufactured at Khadki and possibly at Bolangir.

Aircraft

- This is a list of aircraft of the Indian Army. For the list of aircraft of the Indian Air Force, see List of aircraft of the Indian Air Force.

The Indian Army operates more than 200 helicopters, plus additional unmanned aerial vehicles. The Army Aviation Corps is the main body of the Indian Army for tactical air transport, reconnaissance, and medical evacuation. The Army Aviation operates closely with the Indian Air Force.

| Aircraft | Origin | Type | Versions | In service[50][51] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAL Dhruv | |

utility helicopter | HAL Dhruv | 40+ | ||

| Aérospatiale SA 316 Alouette III | utility helicopter | SA 316B Chetak | 100+ | to be replaced by new LUH, competition to start soon. | |

| Aérospatiale SA 315 Lama | utility helicopter | SA 315B Cheetah | 50+ | to be replaced by new LUH, competition to start soon. | |

| DRDO Nishant | reconnaissance UAV | 12 on order | |||

| IAI Searcher II | reconnaissance UAV | 21 | |||

| IAI Heron II | reconnaissance UAV | 31 |

The Indian army had projected a requirement for a helicopter that can carry loads of up to 75 kg heights of 23,000 feet (7,000 m) on the Siachen Glacier in Jammu and Kashmir. Flying at these heights poses unique challenges due to the rarefied atmosphere. The Indian Army chose the Eurocopter AS 550 for a $550 million contract for 197 light helicopters to replace its ageing fleet of Chetaks and Cheetahs, some of which were inducted more than three decades ago.[52] The deal has however been scrapped amidst allegations of corruption during the bidding process.[53]

Uniforms

The Indian Army camouflage consists of jacket, trousers and cap of coarse cotton material. Jackets are buttoned up with two upper and two lower pockets. Trousers have two front pockets, two cargo pockets and a back pocket. The Indian Army Jungle camouflage dress features a jungle camouflage pattern and is designed for use in woodland and urban environments. The Indian Army Desert camouflage which features a desert camouflage pattern and is designed for use in desert. The Indian Army Desert camouflage is used by artillery and infantry posted in Rajasthan - a desert and semi-desert area.

The forces of the East India Company in India were forced by casualties to dye their white summer tunics to neutral tones, initially a tan called khaki (from the Hindi-Urdu word for "dusty"). This was a temporary measure which became standard in Indian service in the 1880s. Only during the Second Boer War in 1902, did the entire British Army standardise on dun for Service Dress. Indian Army uniform standardizes on dun for khaki.

Recipients of the Param Vir Chakra

Listed below are the most notable people to have received the Param Vir Chakra, the highest military decoration of the Indian Army.

| Major Somnath Sharma | 4th Battalion, Kumaon Regiment | 3 November 1947 | Badgam, Kashmir, India |

| 2 Lieutenant Rama Raghoba Rane | Corps of Engineers | 8 April 1948 | Naushera, Kashmir, India |

| Naik Jadu Nath Singh | 1st Battalion, Rajput Regiment | February 1948 | Naushera, Kashmir, India |

| Company Havildar Major Piru Singh | 6th Battalion, Rajputana Rifles | July 17/18, 1948 | Tithwal, Kashmir, India |

| Lance Naik Karam Singh | 1st Battalion, Sikh Regiment | 13 October 1948 | Tithwal, Kashmir, India |

| Captain Gurbachan Singh Salaria | 3rd Battalion, 1st Gorkha Rifles (The Malaun Regiment) | 5 December 1961 | Elizabethville, Katanga, Congo |

| Major Dhan Singh Thapa | 1st Battalion, 8th Gorkha Rifles | 20 October 1962 | Ladakh, India |

| Subedar Joginder Singh | 1st Battalion, Sikh Regiment | 23 October 1962 | Tongpen La, Northeast Frontier Agency, India |

| Major Shaitan Singh | 13th Battalion, Kumaon Regiment | 18 November 1962 | Rezang La |

| Company Quarter Master Havildar Abdul Hamid | 4th Battalion, The Grenadiers | 10 September 1965 | Chima, Khem Karan Sector |

| Lt Col Ardeshir Burzorji Tarapore | 17th Poona Horse | 15 October 1965 | Phillora, Sialkot Sector, Pakistan |

| Lance Naik Albert Ekka | 14th Battalion, Brigade of the Guards | 3 December 1971 | Gangasagar |

| 2/Lieutenant Arun Khetarpal | 17th Poona Horse | 16 December 1971 | Jarpal, Shakargarh Sector |

| Major Hoshiar Singh | 3rd Battalion, The Grenadiers | 17 December 1971 | Basantar River, Shakargarh Sector |

| Naib Subedar Bana Singh | 8th Battalion, Jammu and Kashmir Light Infantry | 23 June 1987 | Siachen Glacier, Jammu and Kashmir |

| Major Ramaswamy Parmeshwaran | 8th Battalion, Mahar Regiment | 25 November 1987 | Sri Lanka |

| Captain Vikram Batra | 13th Battalion, Jammu and Kashmir Rifles | 6 July 1999 | Point 5140, Point 4875, Kargil Area |

| Lieutenant Manoj Kumar Pandey | 1st Battalion, 11th Gorkha Rifles | 3 July 1999 | Khaluber/Juber Top, Batalik sector, Kargil area, Jammu and Kashmir |

| Grenadier Yogendra Singh Yadav | 18th Battalion, The Grenadiers | 4 July 1999 | Tiger Hill, Kargil area |

| Rifleman Sanjay Kumar | 13th Battalion, Jammu and Kashmir Rifles | 5 July 1999 | Area Flat Top, Kargil Area |

Future developments

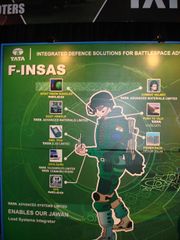

- Futuristic Infantry Soldier As a System (F-INSAS) is the Indian Army's principal modernization program from 2012 to 2020. In the first phase, to be completed by 2012, the infantry soldiers will be equipped with modular weapon systems that will have multi-functions. The Indian Army intends to modernize all of its 465 infantry and paramilitary battalions by 2020 with this program.

- India is currently reorganising its mechanised forces to achieve strategic mobility and high-volume firepower for rapid thrusts into enemy territory. India proposes to progressively induct as many as 248 Arjun MBT and develop and induct the Arjun MKII variant, 1,657 Russian-origin T-90S main-battle tanks (MBTs), apart from the ongoing upgrade of its T-72 fleet. The Army recently placed an order for 4,100 French-origin Milan-2T anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs). Defence ministry sources said the Rs 592-crore (approximately US$120 million) order was cleared after the 2008 Mumbai attacks, with the government finally fast-tracking several military procurement plans.[54]

- The Army gained the Cabinet Committee on Security's approval to raise two new infantry mountain divisions (with around 15,000 combat soldiers each),[55] and an artillery brigade in 2008. These divisions were likely to be armed with ultralight howitzers. In July 2009, it was reported that the Army was advocating a new artillery division, said defence ministry sources.[56] The proposed artillery division, under the Kolkata-based Eastern Command, was to have three brigades—two of 155mm howitzers and one of the Russian "Smerch" and indigenous "Pinaka" multiple-launch rocket systems.

- The Indian Army plans to develop and induct a 155mm indigenous artillery gun within the next three and a half years.[57]

- HAL has obtained a firm order to deliver 114 HAL Light Combat Helicopters to the Indian Army.[58]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "India's Armed Forces, CSIS (Page 24)" (PDF). 25 July 2006. http://www.csis.org/media/csis/pubs/060626_asia_balance_powers.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "General V K Singh takes over as new Indian Army chief". The Times of India. 31 March 2010. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/General-V-K-Singh-takes-over-as-new-Indian-Army-chief-/articleshow/5746561.cms. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ↑ Page, Jeremy. "Comic starts adventure to find war heroes". The Times (9 February 2008).

- ↑ Headquarters Army Training Command. "Indian Army Doctrine". October 2004. Archive link via archive.org (original url: http://indianarmy.nic.in/indianarmydoctrine_1.doc).

- ↑ http://mod.nic.in/aboutus/welcome.html

- ↑ Urlanis, Boris (1971). Wars and Population. Moscow. p. 85.

- ↑ Khanduri, Chandra B. (2006). Thimayya: an amazing life. New Delhi: Knowledge World. pp. 394. ISBN 9788187966364. http://books.google.co.in/books?id=ZWXfAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 30 Jul 2010.

- ↑ For the Punjab Boundary Force, see Daniel P. Marston, 'The Indian Army, Partition, and the Punjab Boundary Force, 1945-47,' War In History November 2009, vol. 16 no. 4 469-505

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Indo-Pakistani War, 1947-1949. ACIG. 29 October 2003. http://www.acig.org/artman/publish/article_321.shtml.

- ↑ Bruce Bueno de Mesquita & David Lalman. War and Reason: Domestic and International Imperatives. Yale University Press (1994), p. 201. ISBN 978-0-300-05922-9.

- ↑ Alastair I. Johnston & Robert S. Ross. New Directions in the Study of China's Foreign Policy. Stanford University Press (2006), p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8047-5363-0.

- ↑ Claude Arpi. India and her neighbourhood: a French observer's views. Har-Anand Publications (2005), p. 186. ISBN 978-81-241-1097-3.

- ↑ CenturyChina,www.centurychina.com/plaboard/uploads/1962war.htm

- ↑ Roger D. Long. "Kashmir dispute". In Encyclopedia of the Developing World (Thomas M. Leonard, editor). Routledge (2006), p. 898. ISBN 978-1-57958-388-0.

- ↑ "1965 Indo-Pak War". Bharat-rakshak.com.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 R.D. Pradhan & Yashwantrao Balwantrao Chavan. 1965 War, the Inside Story: Defence Minister Y.B. Chavan's Diary of India-Pakistan War. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors (2007), p. 47. ISBN 978-81-269-0762-5.

- ↑ Sumit Ganguly. "Pakistan". In India: A Country Study (James Heitzman and Robert L. Worden, editors). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (September 1995).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Indo-Pakistan Wars". Microsoft Encarta 2008. Archived 2009-10-31.

- ↑ Thomas M. Leonard. Encyclopedia of the developing world, Volume 2. Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 0415976634, 9780415976633.

- ↑ Spencer Tucker. Tanks: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO (2004), p. 172. ISBN 978-1-57607-995-9.

- ↑ Sumit Ganguly. Conflict unending: India-Pakistan tensions since 1947. Columbia University Press (2002), p. 45. ISBN 978-0-231-12369-3.

- ↑ Owen Bennett Jones. Pakistan: Eye of the Storm. Yale University Press (2003), p. 177. ISBN 978-0-300-10147-8.

- ↑ Eric H. Arnett. Military capacity and the risk of war: China, India, Pakistan, and Iran. Oxford University Press (1997), p. 134. ISBN 978-0-19-829281-4.

- ↑ S. Paul Kapur. Dangerous deterrent: nuclear weapons proliferation and conflict in South Asia. Stanford University Press (2007), p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8047-5550-4.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Developing World, p. 806.

- ↑ Edward W. Desmond. "The Himalayas War at the Top Of the World". Time (31 July 1989).

- ↑ Vivek Chadha. Low Intensity Conflicts in India: An Analysis. SAGE (2005), p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7619-3325-0.

- ↑ Pradeep Barua. The State at War in South Asia. University of Nebraska Press (2005), p. 256. ISBN 978-0-8032-1344-9.

- ↑ Tim McGirk with Aravind Adiga. "War at the Top of the World". Time (4 May 2005).

- ↑ Sanjay Dutt. War and Peace in Kargil Sector. APH Publishing (2000), p. 389-90. ISBN 978-81-7648-151-9.

- ↑ Nick Easen. Siachen: The world's highest cold war. CNN (17 September 2003).

- ↑ Arun Bhattacharjee. "On Kashmir, hot air and trial balloons". Asia Times (23 September 2004).

- ↑ Indian general praises Pakistani valour at Kargil 5 May 2003 Daily Times, Pakistan

- ↑ Kashmir in the Shadow of War By Robert Wirsing Published by M.E. Sharpe, 2003 ISBN 0-7656-1090-6 pp36

- ↑ Managing Armed Conflicts in the 21st Century By Adekeye Adebajo, Chandra Lekha Sriram Published by Routledge pp192,193

- ↑ The State at War in South Asia By Pradeep Barua Published by U of Nebraska Press Page 261

- ↑ Bitter Chill of Winter - Tariq Ali, London Review of Books

- ↑ Colonel Ravi Nanda (1999). Kargil : A Wake Up Call. Vedams Books. ISBN 81-7095-074-0. Online summary of the Book

- ↑ Alastair Lawson. "Pakistan and the Kashmir militants". BBC News (5 July 1999).

- ↑ A.K. Chakraborty. "Kargil War brings into sharp focus India's commitment to peace". Government of India Press Information Bureau (July 2000).

- ↑ Michael Edward Brown. Offense, defence, and war. MIT Press (2004), p. 393.

- ↑ "Ill-conceived planning by Musharraf led to second major military defeat in Kargil: PML-N". PakTribune (6 August 2006).

- ↑ http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/pastops.shtml

- ↑ http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/brass-tacks.htm

- ↑ http://www.hinduonnet.com/fline/fl1811/18110990.htm

- ↑ Indian Army tests network centric warfare capability in Ashwamedh war games

- ↑ 'Ashwamedha' reinforces importance of foot soldiers

- ↑ Globalsecurity.org, 40 Artillery Division, accessed Jul 2010

- ↑ Army and navy plan to set up a marine brigade

- ↑ Indian military aviation OrBat

- ↑ "Land Forces Site - Army Strength". Bharat-Rakshak. http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/LAND-FORCES/Today/22-Army-Orbat.html.

- ↑ Eurocopter wins big Indian Army deal

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "Indian Army to Purchase 4100 Milan 2T Anti Tank Guided Missiles in USD 120 million Deal". India Defence, 26 January 2009. Accessed 4 January 2010.

- ↑ Pandit, Rajat. "Army to raise 2 mountain units to counter Pak, China". The Times of India, 7 February 2008. Accessed 4 January 2010.

- ↑ Rajat Pandit, Eye on China, is India adding muscle on East? 2 Jul, 2009 0325hrs

- ↑ 155-mm gun contract: DRDO enters the fray

- ↑ Shenoy, Ramnath. "India to test fly light combat helicopters shortly". Press Trust of India, 14 December [2009]. Accessed 4 January 2010.

External links

|

|||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||